| Tennis Home |

| Introduction |

| 1 - The Basic Stroke |

| 2 - Proper Court Position |

| 3 - Defensive Strategy |

| 4 - Offensive Strategy |

| 5 - Serve and Return |

| 6 - Situation Tennis |

| Racquets and Stringing |

|

Tennis for Seniors Author- Richard M. Berger 09/15/2010 All rights reserved You are able to view this book because the author has given you a user name and password to gain access. Please do not copy the book or give your password to others. If you think you know someone who could benefit from this book, please send me their name and e-mail address and I will see that they get a password of their own. My e-mail is: tennis@bergerweb.net Have Fun, and enjoy tennis, the sport for a lifetime. |

| Serving Stroke and Strategy |

The Service Stroke

A player with an NTRP rating of 3.5, at the age of 50, is probably not able to serve faster than about 80 MPH. Maybe one in 50 will be able to top that. By the age of 60, that top speed drops down to around 70 mph. That means that the returner at the opposite baseline has approximately 1.1 seconds to react to the shot, because the average speed of that ball that left the racquet at, say, 75 MPH, is just over 50 MPH. With today's racquets, the senior returner actually has an advantage over the server on most serves. For that reason, placement of the ball on the serve is of paramount importance. The only advice I would give on the service stroke is, "Learn to place the ball where you want it, without giving away your intent." Three factors can help you to do this.

- Toss the ball several feet higher than the place where you intend to strike it.

- Hit the ball with your body and arm fully entended upward.

- Follow through in a straight line toward your target.

Striking the ball as high as possible also makes it easier to get the ball into the service box. If your initial ball speed is 75 miles/hour, you have three times the margin for error if you strike the ball 100 inches above the ground as opposed to striking the ball 90 inches above the ground.

If you concentrate on following through in the direction you intend the ball to go, you will be amazed at how accurate your serve direction can become. When serving, the direction that your racquet is traveling has a significantly greater effect than the angle of the racquet.

Serving Strategy

Each time I watch a doubles match on TV, I will hear at some point, the commentators reiterate the fact that "The best place to serve the ball in doubles is down the middle." There are myriad reasons given, the most common being that serving down the middle allows the serving team to more completely defend against a winning return, because returning a wide ball allows the receiver too much room down the middle. There is some amount of truth in these arguments, but the advantage is not as great as one might think.

A tennis court is 78 feet long, divided in the middle by a net. The width of the doubles court is 36 feet... 18 feet each side of the center mark on the baseline.

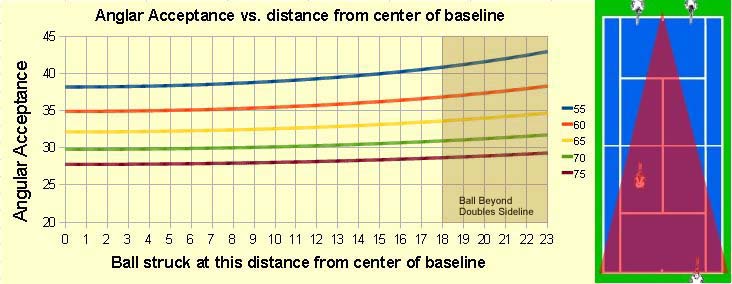

The chart above shows the acceptance angle (number of degrees that a ball can be hit and still land in the court) when hit from various points along the baseline. The lines at the zero point on the horizontal axis represents a ball hit from the center of the baseline which has a carry distance (distance traveled before it bounces) of 55, 60, 65, 70, and 75 feet. (red shaded area on the court diagram [right side]). The "18" point on the horizontal axis represents a ball hit from behind the doubles sideline, and the "23" point corresponds to a ball hit from 5 feet outside the doubles sideline. The vertical axis shows the angle at which the ball may be hit and still land within the opponents court, providing the ball travels the distance represented by the various colored lines on the graph. The yellow line shows that a ball that travels 65 feet in the air, hit from the center of the baseline, has an acceptance angle of about 32 degrees. The player could strike a ball at the center of the baseline and angle it anywhere from 16 degrees right to 16 degrees left, and if it traveled no more than 65 feet, it would land inside the opponents court. If a ball were hit the same distance, but from behind the right doubles sideline, It could be hit at an angle of 0 degrees (down the line) to 33.6 degrees (crosscourt) and still land in the opponent's court. If you served a ball really wide, and the opponent had to strike it 5 feet outside the doubles sideline, he would have an acceptance angle of almost 35 degrees. As you can see, there is a small advantage to serving the ball down the center, as opposed to wide, but it is minor, compared to the advantage you gain by being able to make the opponent guess which direction you will serve. In addition, more experienced doubles teams will return serve with their best strokes protecting the center of the court, so serving the ball down the center will usually mean hitting to the opponent's strength. One other point should be noted about balls that aren't hit deep, but are hit at a large angle crosscourt. Even though the chart shows that the ball that travels only 55 feet would have an acceptance angle of almost 41 degrees when hit from behind the doubles sideline, that ball would land short of the net if hit crosscourt.

It's important that your partner knows where you are going to place the serve, for he will have a specific area of the court that he must protect against the return. If your serve will be down the center, he will want to be around the center of his service box when the opponent strikes the return. If you are serving wide, he will want to be a step toward the sideline from the center. This position still tempts the opponent with a small sliver of the alley into which he may hit the return, but for the average ball, the opponent has only plus or minus 2 degrees of available error for that shot, and it's more important to protect the center than the sidelines. Down the middle, the opponent can make a large error left or right, and your team will still have to play the ball. On the outside, he can err in one direction and you will have to play the ball, but if he errs too much in the other direction, the ball is OUT!

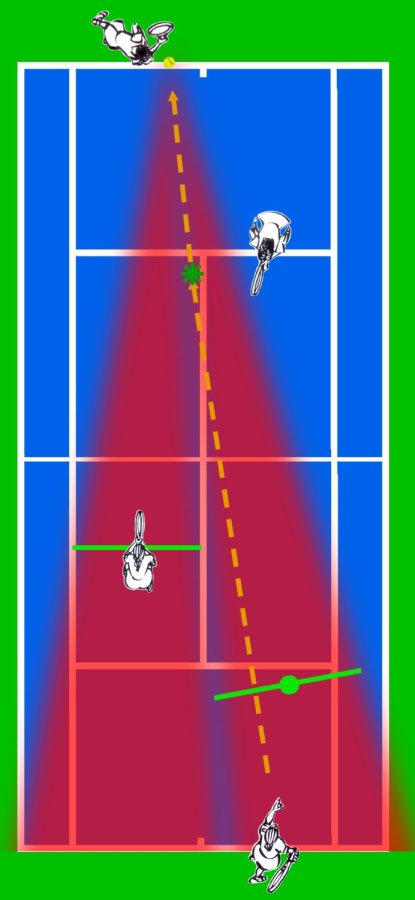

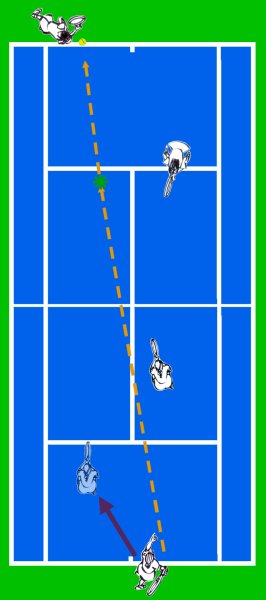

Let's take a look at how the service team should cover the possible returns of both wide serves, and serves down the center of the court. The diagram to the left illustrates how the serving team should position themselves to cover the return of a ball served down the middle. Note that the net person starts out near the center of his service box and stays there, while the server, once he strikes the ball, must move forward to the position indicated by the green dot with the "wings" attached. The wings indicate the "curtain" of protection that each player can cover, given the amount of time they have available after the returner strikes the ball. The "curtain" for each player represents a total of about 13 degrees.

Let's take a look at how the service team should cover the possible returns of both wide serves, and serves down the center of the court. The diagram to the left illustrates how the serving team should position themselves to cover the return of a ball served down the middle. Note that the net person starts out near the center of his service box and stays there, while the server, once he strikes the ball, must move forward to the position indicated by the green dot with the "wings" attached. The wings indicate the "curtain" of protection that each player can cover, given the amount of time they have available after the returner strikes the ball. The "curtain" for each player represents a total of about 13 degrees.

Note how the red coverage area fades near the edges of each player's reach, which is representative of the fact that although the players can cover these angles, their shots may not be as agressive. Note that the serving team is leaving open a few degrees on each side, but only a marginal amount down the center.

Note how the red coverage area fades near the edges of each player's reach, which is representative of the fact that although the players can cover these angles, their shots may not be as agressive. Note that the serving team is leaving open a few degrees on each side, but only a marginal amount down the center.

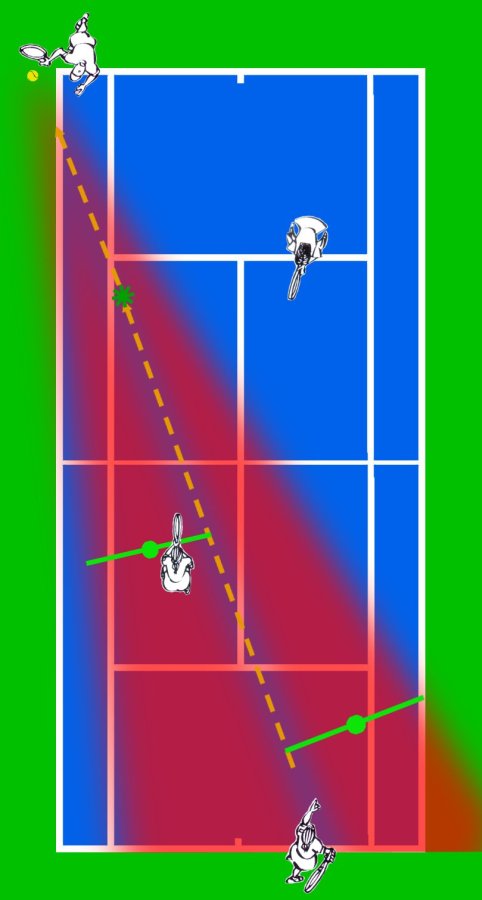

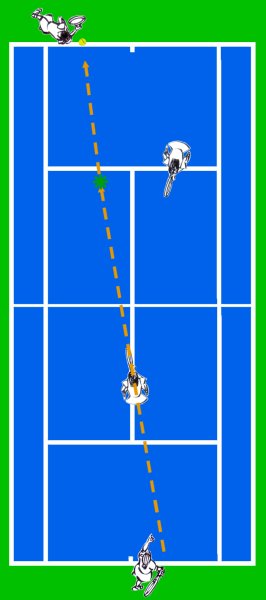

The graphic to the right represents what the serving team must do to cover returns of a wide serve. Note how the net person must move a step to the left to cover most of the down-the-line possibilities, while the server must move farther right, because now there is more area to cover if the returner goes crosscourt. The serving team is still covering 13 degrees each, but now the returner has a small amount of extra space on each side into which to place the ball. There seems to be a lot of space available to the right of the server, but remember that in order to keep the return from going long, the returner must take pace off the ball, giving the server more time to chase it down.

Poaching

Poaching is one of the most overlooked skills in adult and senior tennis. In professional tennis, the server's partner poaches quite often because it is an effective way of winning points very quickly. But to be good at poaching, certain skills are required. You must know when to make your move, and in which direction. (yes, direction counts)

Anytime you are going to poach, let your partner know what you are going to do. It's true that many pros prefer to poach spontaneously, but I think I mentioned very early in this book that senior

players are set in their ways. We don't react as quickly to changes as youthful players. Your partner needs to know from the beginning of his service motion that she must cover the side of court that you vacate when you poach. That's not to say that if the return is close enough that you can put it away, you shouldn't take the opportunity, but If you are planning to cross the center line by a full step, your partner needs to cover behind you.

players are set in their ways. We don't react as quickly to changes as youthful players. Your partner needs to know from the beginning of his service motion that she must cover the side of court that you vacate when you poach. That's not to say that if the return is close enough that you can put it away, you shouldn't take the opportunity, but If you are planning to cross the center line by a full step, your partner needs to cover behind you.

To prepare for the poach, time your split step so that you land just an instant after the serve bounces, and begin your move immediately thereafter. Any sooner, and the opponent will be able to easily adjust his return to keep it away from you. Any later, and you won't have time to cover enough ground to get to the ball. Move toward the net at an angle, not just sideways. You need to take the ball near the net so that your opponents don't have much time to react to your shot. Also remember that your best target is an angle shot into the alley you are headed toward. This isolates the opposing net person, who has little time to react to your shot, and you can continue toward the sideline to cover any possible down-the-line play that she takes. Meanwhile, your partner will have moved into position to cover the crosscourt and middle shot. The key to your success lies in your placement of the ball. You will be moving quickly, and won't be able to reverse directions, so as we said in a previous chapter, keep the ball in front of you.

If you are the server and your partner has told you she is going to poach all out, you have three very important tasks.

- Place the serve near the center of the court.

- Cover the side of the court that your partner vacated.

- Watch for an aborted poach.

The Australian Formation

The Australian Formation is a serving tactic that can be particularly effective when the opponent has a good crosscourt return-of-serve. It has advantages and disadvantages compared to the poach. The main disadvantage is that the returner knows that your net person is covering the cross-court shot. The advantages are

* The server knows that his partner is covering the crosscourt shot

* The serving team can defend a larger portion of their court.

* To avoid the net person, the opponent must return the ball over the higher part of the net.

* To hit a winner, the opponent must direct the ball toward the sidelines.

* The server has more choices as to where she may place the serve.

When using the Australian formation, don't try to disguise your purpose. Serve the ball from near the center of the baseline, and make your opponent guess where you will place the serve. If they have a weak side, favor that placement. As soon as you serve, move over to cover the down-the-line shot, but don't forget to split-step so you can cover a center shot that gets past your partner at net. Your partner will have taken up a position that allows her to cover almost any cross-court return, and some of the center. She won't have to move. Your opponent has two openings if she is able to place the ball very near either sideline, but her chances are minimal. Using the Australian formation gives your net person a bit more time to handle a ball aimed at her, due to the lateral distance the ball must travel. At the same time, the server has more time to react, since she is covering a ball that must pass over a higher part of the net.

Given all the advantages of the Australian formation, it's odd that club pros don't stress the importance of learning to use it. With the exception of the fact that the server has to move slightly further to get into the ideal volley position, the advantages of this formation far outweigh the disadvantages, especially against players who like to hit low, slice returns over the center of the net. If you are going to serve and remain at the baseline, the advantage of your partner covering returns over the lower part of the net are tremendous.

The "I" Formation

Over the course of 5 years, the "I" formation has become almost as popular as the regular serving formation for men's professional doubles teams. Every touring team has adopted this formation. At a recent professional women's match, I noted that one team used the "I" formation on every serve against one of the opponents, and won all but one of those points.

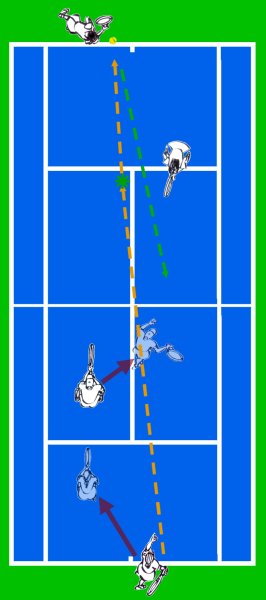

As shown in the diagram at the left, the "I" formation differs only slightly from the Australian formation. Instead of the net player starting in the same court as the server, she takes a low position on the center stripe, a couple of feet nearer the service line than the net. The server and her partner have already agreed which of them will cover each side of the court. As the receiver is about to strike the ball, the server's partner moves either left or right a step or two, and as in the Australian formation, the server covers the side of the court not covered by the net person. This requires some well-timed movement by both the server and her partner, but the opponent has little time to react to the two possibilities, and must guess where best to direct the return.

If you want to use this formation in match play, I recommend you put in several hours of practice before hand. There is nothing like experience to prepare you for the possible returns you are likely to face. The most common mistake most inexperienced teams make is leaving the center of the court open. Remember that both the server and her partner will be moving away from the center of the court, and If the opponent directs her return over the center, at least one player must reverse directions to cover that shot. If you and your partner have become very proficient at split-stepping on every shot, you shouldn't have any trouble, but for a lot of seniors, the first step to using the "I" formation is mastering the split-step.

Defending Against the "I" and Australian Formations

When you run up against someone who is using the Australian formation, it is generally because you have a cross-court return that they cannot handle. Don't panic! All you need do is adjust your targets. Whether you play the ad court or the deuce court, when the server moves to the center of the service line, adjust your position toward the center of the court so you can cover the center serve. Your partner should also adjust his position. Instead of his normal position just behind the service line, he should move up into the service box in front of him, and very near the center service line. As the returner, you can either lob the ball over the net player, or play the ball down the line. Don't be a fool and try to jam the ball down the throat of the net person, or try a cross-court shot into the tiny sliver of alley left open by the net person.

Against the "I" formation, you need to take a couple of steps back to give yourself additional time to read your opponent's movements. It's usually better to focus on the server, because he is the one who must begin his motion toward one side or the other first. If you notice the server moving left, immediately make your decision, and go to the left, keeping the ball away from the net man. Likewise, if the server moves right, hit the ball toward the right. The key is to make your decision as early as possible, and then concentrate on nothing more than that tiny target at the back side of the ball.

What if you simply have to defend against a monster serve, where all you have time for is blocking the ball back in play. When you face a server like this, your best bet is to start the point with both the receiver and his partner behind the baseline. Then you at least have a chance of keeping the point alive if the returner can't keep the ball away from the opposing net person. Worry about gaining the ideal volley position once you have put the ball in play.